Exploring Chinese influence in Pre-Columbian America

Cultural echoes and shared knowledge hint at Chinese influence in pre-Columbian America

Resistance from Western academia stems from entrenched narratives of Eurocentric discovery

Indigenous oral traditions and art may preserve the memory of encounters long absent from written history

By Sebastian Lim

IN Part 1, Dr Sheng-Wei Wang introduced the theory that the famed Chinese admiral Zheng He may have sailed to the Americas in the early 15th century — decades before Columbus. Through maps, maritime records, and artifacts, she laid the groundwork for reconsidering our assumptions about who first discovered the New World.

In this second part of the interview, Dr Wang shares further insight into the clues she’s assembled — ranging from DNA and linguistic evidence to ocean currents and cultural memory. Her work not only challenges historical orthodoxy but also points to the need for a more globally inclusive understanding of early human explorations.

Knowing that Zheng He's mariners had reached the Americas and that some of them might have decided to stay on and settle down there, and then got married, could have worldwide ramifications. As in the possibility of East Asian DNA markers appearing among some Native American populations.

Dr. Sheng-Wei Wang says: "The renewed interest in Zheng He is about restoring a lost legacy. Zheng He’s peaceful exploration offers an alternative narrative to Western views."

“I would like the academics to take a fresh look at my work and to initiate new progress and direction towards establishing the theory that Zheng He’s mariners may have navigated the whole world,” says Dr Wang.

She also stresses the importance of cultural continuity and memory — particularly among indigenous communities whose oral traditions reference ancient visitors from across the sea. “Such memories are valuable,” she notes. “They are encoded in songs, rituals, and legends.

For example, tribes along the northeast coast of the Americas have stories of strangers who arrived in large ships and brought advanced tools or knowledge. These are not merely coincidences.”

Why did the voyages stop?

If Zheng He or his successors had indeed reached the Americas, the next logical question is: Why were these monumental voyages not continued or documented in greater detail? Dr Wang attributes this to a major policy shift in China after 1433. “Zheng He’s last voyage ended just before a period of isolationism under the new emperor,” she explains.

“The Ming court suddenly stopped further expeditions due to its high cost and Mongol threats at the country’s northern borders. Records were destroyed. That was the end of China’s great maritime era.”

Indeed, historians have confirmed that following the death of Emperor Yongle — Zheng He’s patron — the Ming Dynasty sharply curtailed naval ambitions soon after the seventh voyage ordered by Emperor Yongle’s grandson, Emperor Xuande.

Ancient trade routes and maritime knowledge

Dr Wang’s research also considers the practical navigational routes that Zheng He’s fleet might have taken to reach the Americas. She points out that ocean currents, particularly the Agulhas Current, could have carried Chinese ships from East Africa to South Africa, followed by the Benguela Current to round the southern tip of Africa and to reach the east coast of North, Central or South America; and the Brazil Current could also have carried the Chinese ships from the northeast coast of South America towards the south, the South Pacific Current then facilitated rounding the southern tip of the Americas, and finally the South Equatorial Current could have brought these ships towards New Zealand, Australia and Asia.

“We underestimate ancient mariners,” she says. “They understood currents, winds, and stars. Zheng He’s fleet had highly skilled navigators. They knew how to ride the monsoons to India and Africa. It's not unreasonable to believe they could follow currents across the Atlantic and the Pacific.”

Some historical accounts describe Chinese ships of the era as remarkably advanced — far larger and more technologically sophisticated than those of contemporary European powers. The Ming fleet used watertight bulkheads, stern-post rudders, and advanced hull designs, and included durable food supplies, all of which made long-distance ocean travel feasible.

Dr Wang further speculates that Zheng He’s expeditions, which were diplomatic and trade-oriented, may have left behind goods or technologies that influenced indigenous societies.

Evidence in the Americas: artifacts

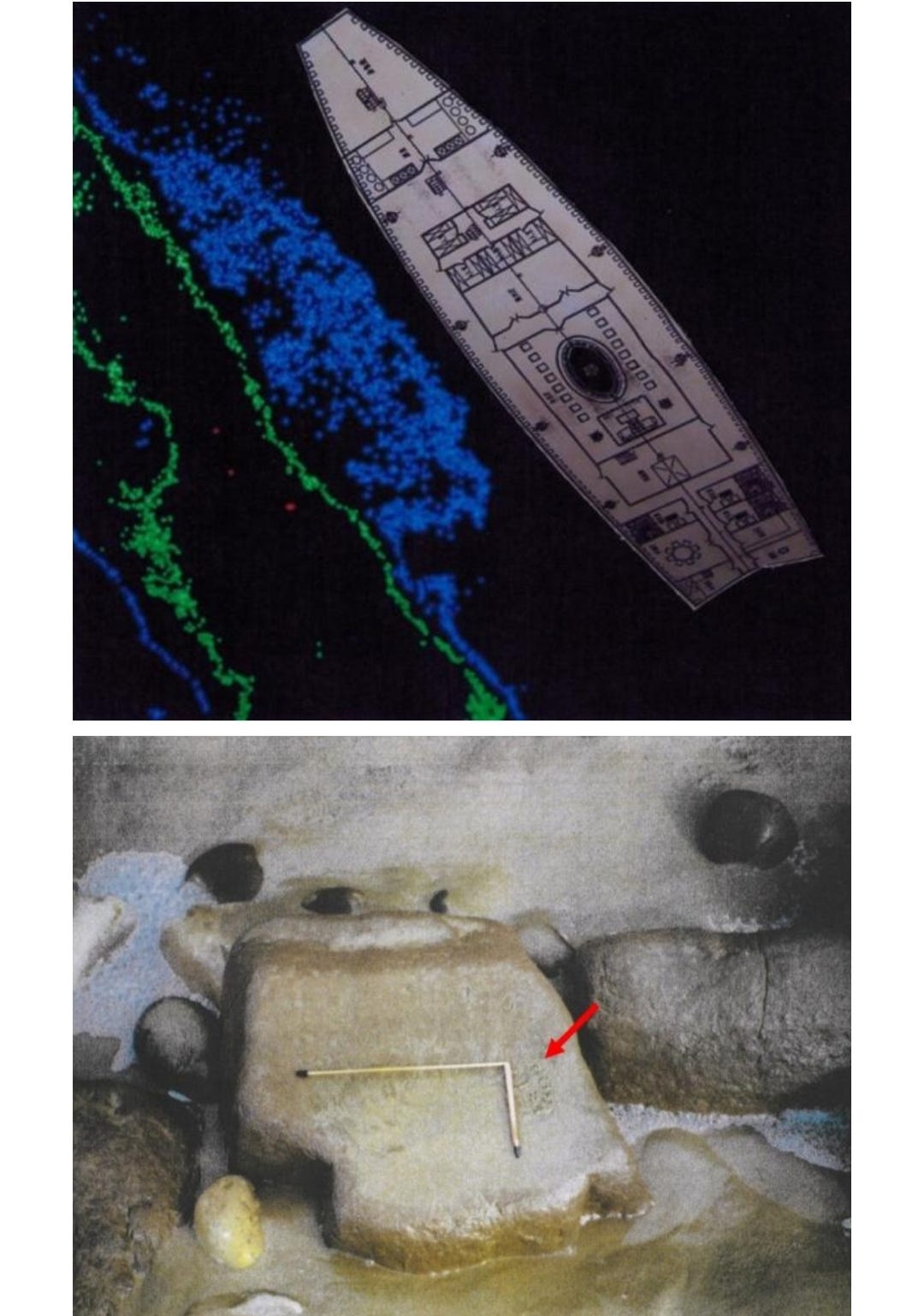

Beyond maritime logic, Dr Wang is well informed of intriguing anecdotal and material clues. These include reported discoveries of Chinese-style jade carvings, porcelain shards, and ship anchors along parts of the American coastline. Though not widely accepted in mainstream archaeology, such items provoke curiosity.

“Some of the artifacts appear to predate European contact,” Dr Wang explains. “If verified, they could suggest early contact with East Asians. These findings are scattered and not always easy to date precisely, but they are worth investigating.”

Scholarly resistance and the need for openness

Despite the breadth of evidence gathered, Dr Wang is well aware of the resistance such theories face. “Mainstream academia has not been kind to alternative hypotheses,” she admits. “There is a reluctance to challenge Eurocentric narratives.”

Dr Wang credits Gavin Menzies with sparking public interest but distances her work from his more speculative claims. “He had the right idea but lacked evidence,” she notes. “I brought scientific rigour — verifying every name, coordinate, and inscription.”

Reclaiming maritime legacy

Why does any of this matter today? For Dr Wang, it is about restoring a lost legacy. “Zheng He’s peaceful exploration offers an alternative narrative to Western views,” she says.

She draws a parallel with China’s 21st-century Belt and Road Initiative. “It’s the modern version of the treasure fleet — uniting continents through trade and friendship, not force.”

“The Maritime Silk Road builds on the maritime expedition routes which Zheng He established over 600 years ago,“ says Dr Wang. “It could be viewed as a modern version of Zheng He’s trade and diplomacy.”

Call to reimagine history

As the world grows more connected, Dr Wang sees a growing appetite for untold stories and hidden histories. She hopes her work will inspire younger generations to look beyond conventional textbooks.

“We must reimagine the past,” she says. “The oceans didn’t separate civilisations — they connected them. Zheng He’s voyages represent not just China’s maritime glory, but a lost opportunity for deeper human exchange.”

Dr Wang believes it’s time to ask bold questions and explore inconvenient possibilities. She hopes her work will help foster greater understanding between East Asia and the Americas.

"If Chinese explorers reached the New World centuries ago, it shows we have long been connected,” she says. “Let’s build on that shared heritage.”

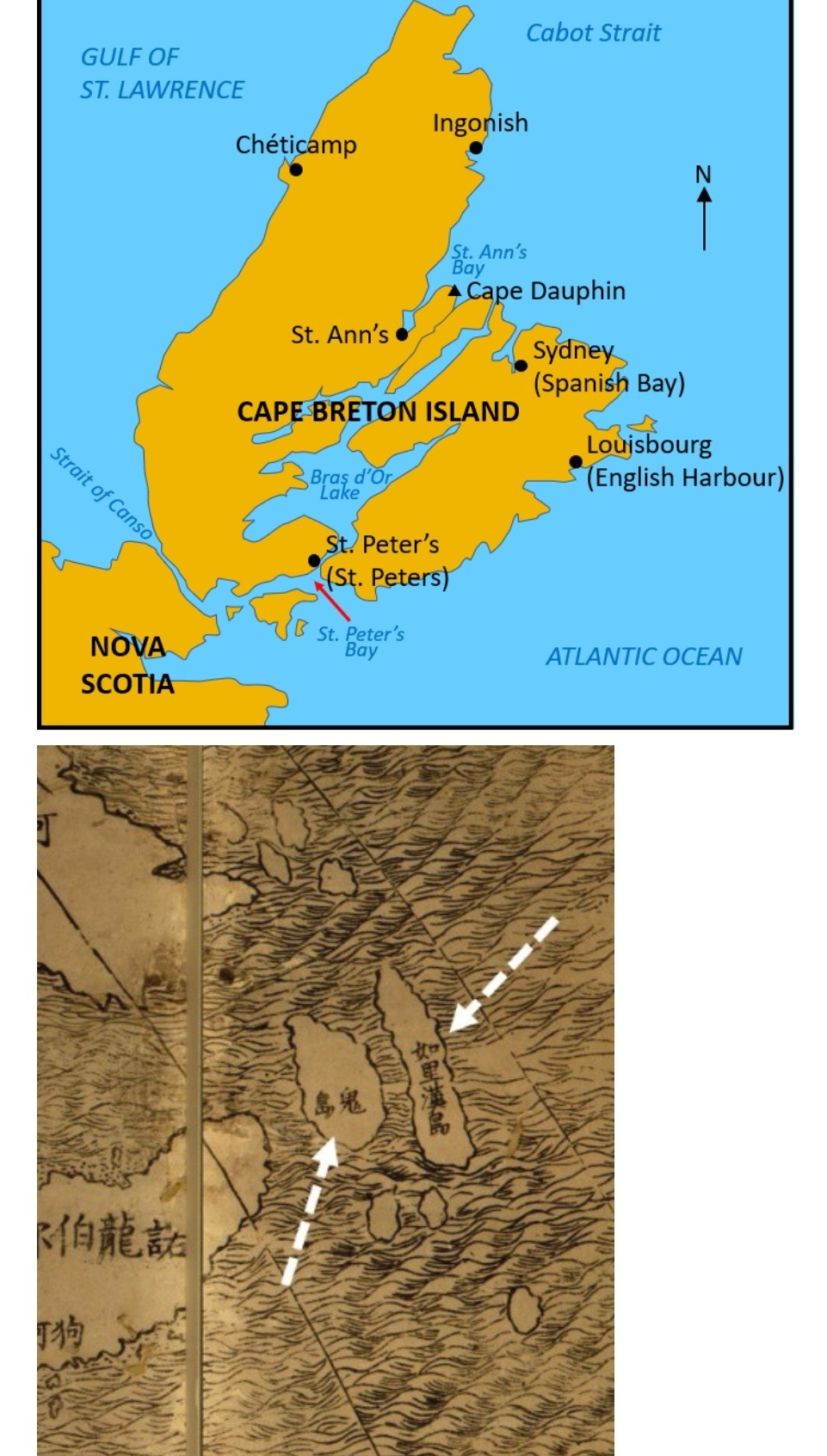

Her final message to scholars? “Read the maps. Visit the sites.”

"My vision is that I see a map as not only a record of geographical locations but a vivid replay of history on paper. The true history is carried by each marking. If you have the patience and knowledge to uncover it, you will get to the truth.”

All articles, opinions, and events featured in PostScript NAC represent the views of the interviewees, individual writers and contributors, and do not necessarily reflect those of PostScript NAC. While we strive to ensure all information on this post is accurate, complete, and current, PostScript NAC is not responsible for any errors, omissions, or outdated content.